In his latest solo exhibition in Kuala Lumpur, contemporary artist Chang Yoong Chia delves into the stories of a nation shaped by a past often forgotten and a tradition that transcends time.

In A Leaf Through History, which is showing at Cult Gallery in Bukit Tunku, he continues his exploration of the batik technique and its evolution, and reflects on the influence of cash crops on the country, its people and wildlife.

This body of work comprises mostly batik pieces, with a few pencil sketches and watercolour works.

Merging historical facts with imagination, Chang has put together a show that embraces the complexities that come with different perspectives and versions of Malaysian history.

The storyteller side of the artist makes a strong appearance in this exhibition as he peels layer after layer of the past.

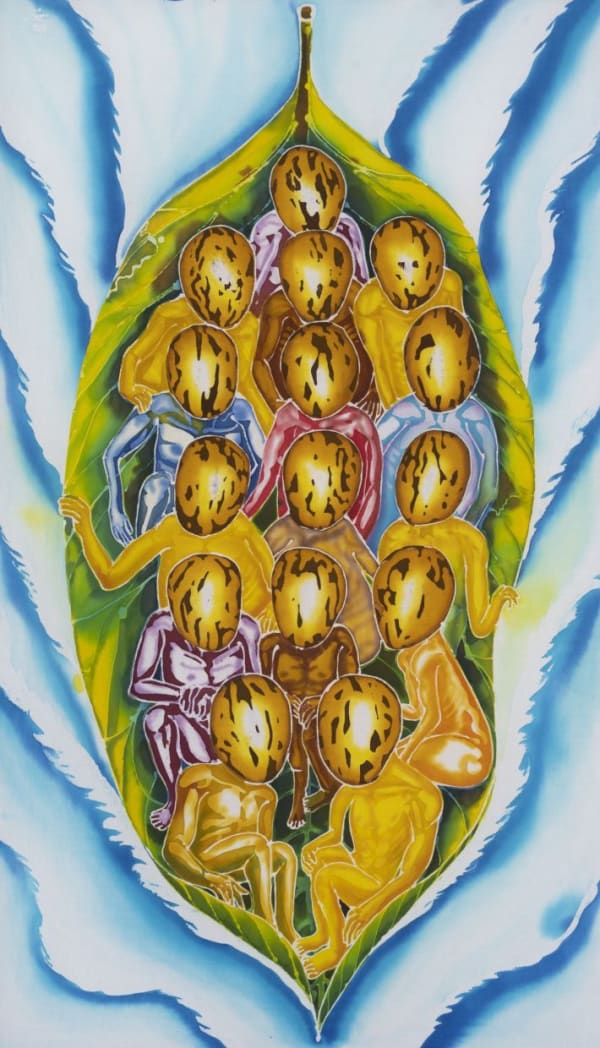

Chang’s moving away from the popular flower motifs of local batik to the depiction of cash crops of our land (rubber, gambir, oil palm) is a deliberate one, as it is with his inclusion of the stories of the common man – from exhausted rubber tappers, the hungry, tapioca-eating days during WWII and the mighty beasts of the forests (tiger, orang utan) which are now endangered.

“Through these works, I wanted to explore some key events in the history of Malaysia and how these events affected our lives. I also wanted to shine a light on the people who laboured in these plantations, as well as the changes in the ecosystem and wildlife,” says Chang, 47, who uses personal narrative and memory as a subjective space to explore the imaginative possibilities of painting and object-making.

During his research on Malaysian batik, he often came across statements that plant motifs are most commonly used.

“So I decided to use the cash crops plants of Malaysia for my motifs, because plantations are found all over Malaysia but very seldom portrayed in batik,” he says.

Chang’s recent batik art installation at the Ilham Art Show 2022 (which runs at KL’s Ilham Gallery till October) is part of his A Leaf Through History batik series. Each of the 28 individual pieces that make up the whole, depicts a rubber tree which is also human.

Batik is a relatively new venture for him, one that he first thought about exploring when he saw Ilham Gallery’s group exhibition Love Me In My Batik in 2016, a multi-generational survey of batik artists.

“The show sparked memories of batik paintings I saw growing up that I have nearly forgotten, which led me to my journey of experimenting with batik. When the Ilham Art Show open call was announced (last year), I submitted my proposal for an installation that suggests the vastness of a rubber plantation.

"I thought it would be nice to exhibit at the same venue that inspired this series. Luckily, my proposal was accepted,” says Chang, who majored in painting, and has used that skill to full effect in this new exhibition.

National fabric

A Leaf Through History exhibit at Cult Gallery features two works – Family Tree (Study I) and Family Tree (Study II) – that are similar to the artworks on display at the Ilham Art Show.

Unsurprisingly, one of the themes explored in this exhibition is batik as a national identity.

In the course of Chang unpacking how Malaysian batik is synonymous with Malaysian cultural identity, he ended up with more questions than answers.

“What exactly is our cultural identity? Is it an idea that is reinforced by external forces or is it a feeling that comes from within? Is there a common ground between batik paintings that belong in the realm of fine art and the batik in the textile and fashion industry?

“How do different genders, age groups or ethnicities think and use batik in their lives? As more questions began to crop up, I thought, instead of trying to find answers, why not just make a series of batik works that prompts people to ask questions about our collective identity?” he says.

Contrary to popular belief that new ideas will lead us to “forget” about our tradition, he thinks that having a broader idea about the traditional will instead help reinforce our own dialogue with tradition and what it means to us.

“It also allows younger people who are interested to learn about traditional crafts to enter into the dialogue more on their own terms. Having said that, I deeply respect the batik master artisans and batik painters. It’s a complicated skill to master as it requires a lot of knowledge, experience and dedication,” he adds.

Away from Kuala Lumpur

Last year, Chang moved from Kuala Lumpur to small town Tangkak in Johor, in search of a simpler life and to focus on art making. His surroundings there directly influenced his new works.

“After my batik residency in Kelantan in 2020, I wanted to work on some ideas based on my experience there. But everything changed because of the pandemic. Because I was confined in Tangkak for about six months because of the lockdown, I started to really look around my immediate environment. There are a lot of plantations surrounding Tangkak, so the idea of using cash crops as batik motifs and subject matter came because I am living here,” he shares.

Still, there is still a bit of his residency in this exhibition, in the form of Kelapa Kepala I, which he made in Kota Baru after visiting the first landing site of the Japanese invasion at Pulau Pak Amat beach just after midnight on Dec 8, 1941, before the attack on Pearl Harbor in the United States.

There are many more eye-opening stories in A Leaf Through History, like in The Dyeing Era, which captures the dangers faced by those working in gambir plantations in the early 1800s.

“The workers worked under threat of tiger attacks. But now gambir, which was used for dyeing cloth and tanning leather, is no longer planted in Malaysia and the Malayan tiger is on the brink of extinction,” he says.

Another piece, Olfactory Memory is a rumination on how the stench of latex is such a prevalent and intense memory for those who have worked in a rubber plantation, something that escapes Chang as it is not something he has experienced.

“I am unable to imagine this olfactory memory, which makes me wonder what other hidden details are unattainable even if one is well-informed through reading archival material. This artwork is also a sarong, with a diagonal band that separates the top design from the bottom.

“You can wear it in different ways depending on whether you want the top or bottom portion to be visible. In this show, I also wanted to explore batik as clothing. The sarong was once an important clothing item which also functions as a screen to change clothes in, a picnic mat on the beach, or an extra blanket,” he says.

Olfactory Memory is one of four batik sarongs showcased in this exhibition.

Lastly, among the striking batik works are three small pieces where Chang delicately paints on rubber leaves with holes in them.

“While working with small and fragile organic materials, I need to tense my muscles and breathe carefully. That makes me more aware of my own body. I also like the idea that when it passes on to somebody else, the person has to take good care of it, protecting it.

“These three works are made towards the end of the series. Up until this point, I had been focused on images that tell the stories of plantation history.

"So I thought it would be a good idea to just let the shape of the leaves inspire me and hope by doing that, the series ends with an open-ended possibility,” he concludes.

Original artical can be found at